|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The passing tourist often makes an about-‐turn when he catches

sight of this superb chapel surrounded by olive trees. Particularly if he is

passing a little late in the afternoon the incomparable hue of the stone will

immediately dazzle his eyes. All due to the beauty of the chapel. Or rather our

church because its dimensions are quite substantial. Moreover, Prosper Merimee

in his book ‘Notes on a journey through the South of France’ in 1835 described

it as a church.

This same Prosper Merimee, recognizing the importance of the structure,

included it in 1840 in the very first listing of historical monuments.

Saint-Gabriel (under the heading of chapel) appeared in this list with 933

other structures deserving of proper maintenance as part of their conservation.

The chapel is listed alongside cathedrals such as Laon, Narbonne, Aix en

Provence, Angouleme, Senlis, Auxerre, Sens, Notre Dame des Dons in Avignon as

well as abbeys such as Conques or closer to home Montmajor, and chateaux such

as Amboise, Chinon, Chenonceau, Chambord or Blois, the amphitheatres of Arles

and Nimes, the pont du Gard, the pont d’Avignon, and even the Palace of the

Popes. Very select company indeed.

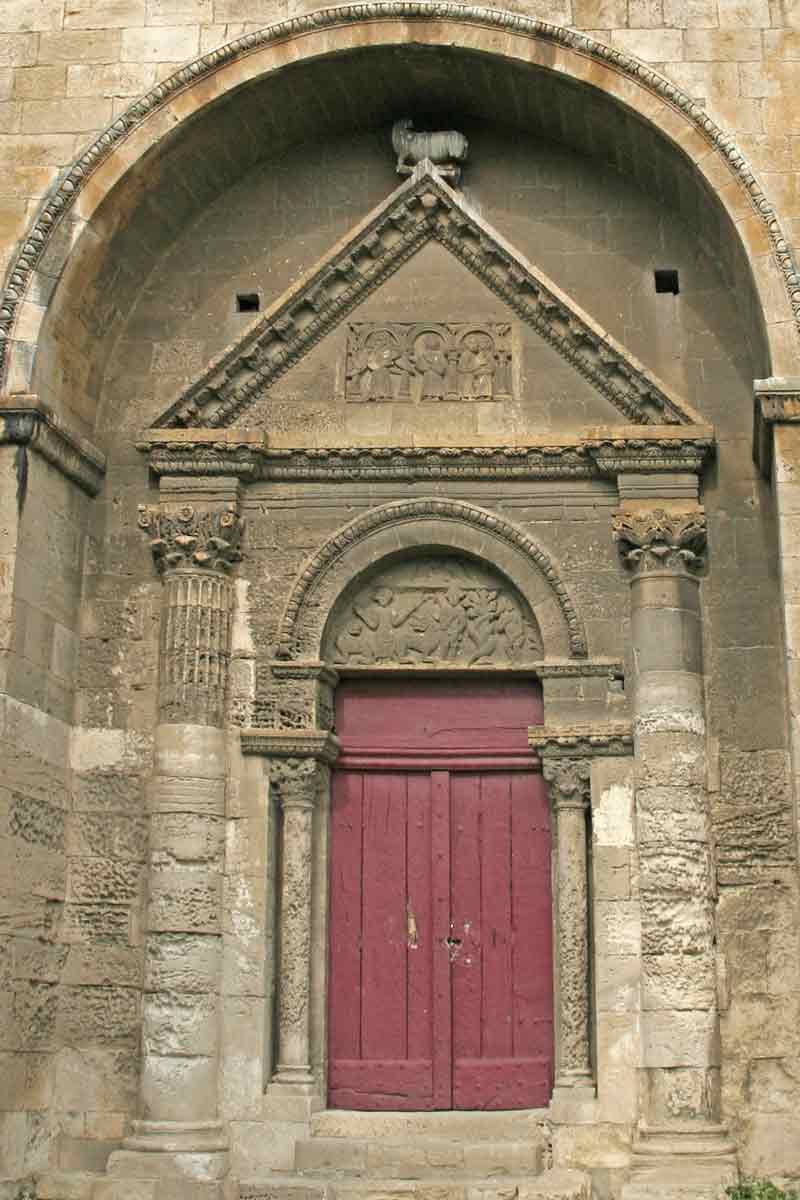

Visitors who know Roman art are immediately amazed by the richness of

the decoration of the façade, rare for a Roman construction at the end of the

12th century.

Details of the façade.

Above the door the semi-circular typanum mounted on two small columns

represents Daniel on the left accompanied by two lions then the angel holding

Habaquq by the hair who has been given the task of bringing a basket of food to

Daniel. On the right Adam and Eve and here and there the serpent entwined

around a fig tree hiding their nakedness after they have succumbed to

temptation.

Around the entrance porch two columns with Corinthian capitals decorated

with acanthus leaves support a triangular pediment with the Easter lamb atop.

The position of this latter statue, which gives the appearance of being

squashed, is hardly aesthetic. This suggests it was brought from elsewhere and

placed here.

On the pediment to the left and in the centre the Annunciation by the Archangel Gabriel to Mary.

On the right the visitation of Mary to Elizabeth who recognizes her as the mother of the Messiah and kisses her. The

characters are framed in three arches with four birds in the recesses above, three of the birds have fruit in their beaks.

Part of a fourth arch on the left suggests that this bas-relief had previously been used elsewhere. The inscriptions cut into

the stone are identical to those found on the interior and exterior walls

of the chapel.

One oddity. In his ‘Notes on a journey through the South of France’ Prosper Merimee describes the pediment thus: ‘The tympanum of this pediment contains another square bas-relief, representing the appearance of the Angel Gabriel to the Virgin ... The Angel, contrary to general custom in the 12th century, is almost entirely naked.’

On this occasion he has got it wrong. He

must have mixed his notes up...

On the upper part an archivolt, very simple in its structure and off-centre in relation to the roof, sits a superb and imposing circular window (oculus) decorated with leaves and ten very detailed faces of men and women some of which are in an exceptionally good state of repair.

On the four points of the compass the tetramorph (the four disciples in

their allegorical form): John (the eagle), Luke (the bull), Matthew (the man)

and Mark (the lion). In terms of symbolism the man is Matthew because his

gospel began with the genealogy of Jesus. The lion is Mark because his gospel

began with the cry of St John the Baptist in the wilderness. As for Luke as the

bull this is because his gospel begins with Zachariah offering a sacrifice to God (it was often

an ox). And finally John as the eagle because of the celestial mystery of his

gospel, a prologue on the Word. A voice cometh from heaven. A great view from

on high ... hence the eagle.

The tetramorph reflects the stages in the life of Christ: Incarnation as

man, Sacrifice with the ox, Resurrection with the lion, and Ascension to heaven

with the eagle.

It is extremely rare to find a tetramorph in the form of a cross. Very

often it is either in an X or a U form. As with all tetramorphs the four

statues have wings which explains why many visitors mistakenly take Matthew for

the Archangel Gabriel.

At the back of the chapel a very simple five-sided chevet covered with flat roofing stones (as is the whole of the structure) and incorporating an opening which permits a view of the interior when the chapel is closed. In the morning sunlight enters by this opening and bathes the interior with a wonderful glow.

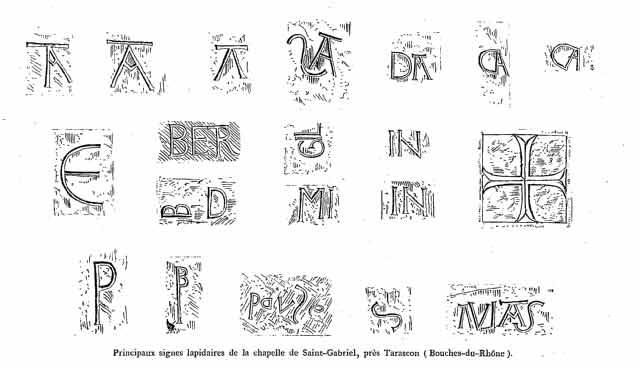

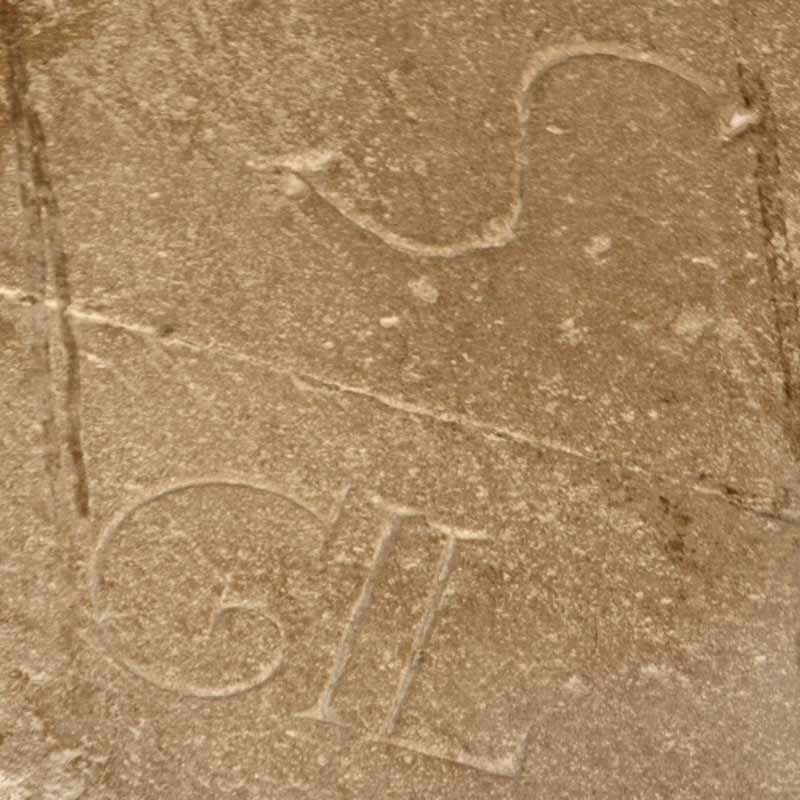

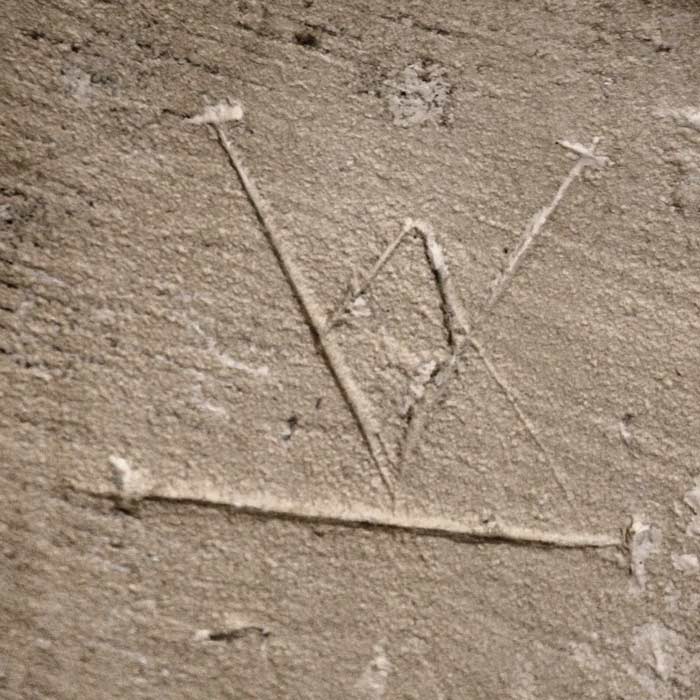

The whole structure, both internal and external, is peppered with insignia cut into the stone, generally discreetly placed and generally finely shaped. There’s about a hundred in total with 30 different variations that any visitor will find entertainment in their discovery. These insignia, as well as their type of cut, together with comparisons with similar Roman edifices in the South of France, have enabled the construction date of the chapel to be determined.

Tailles.

The controversy

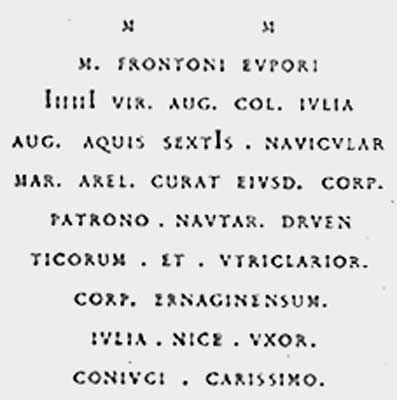

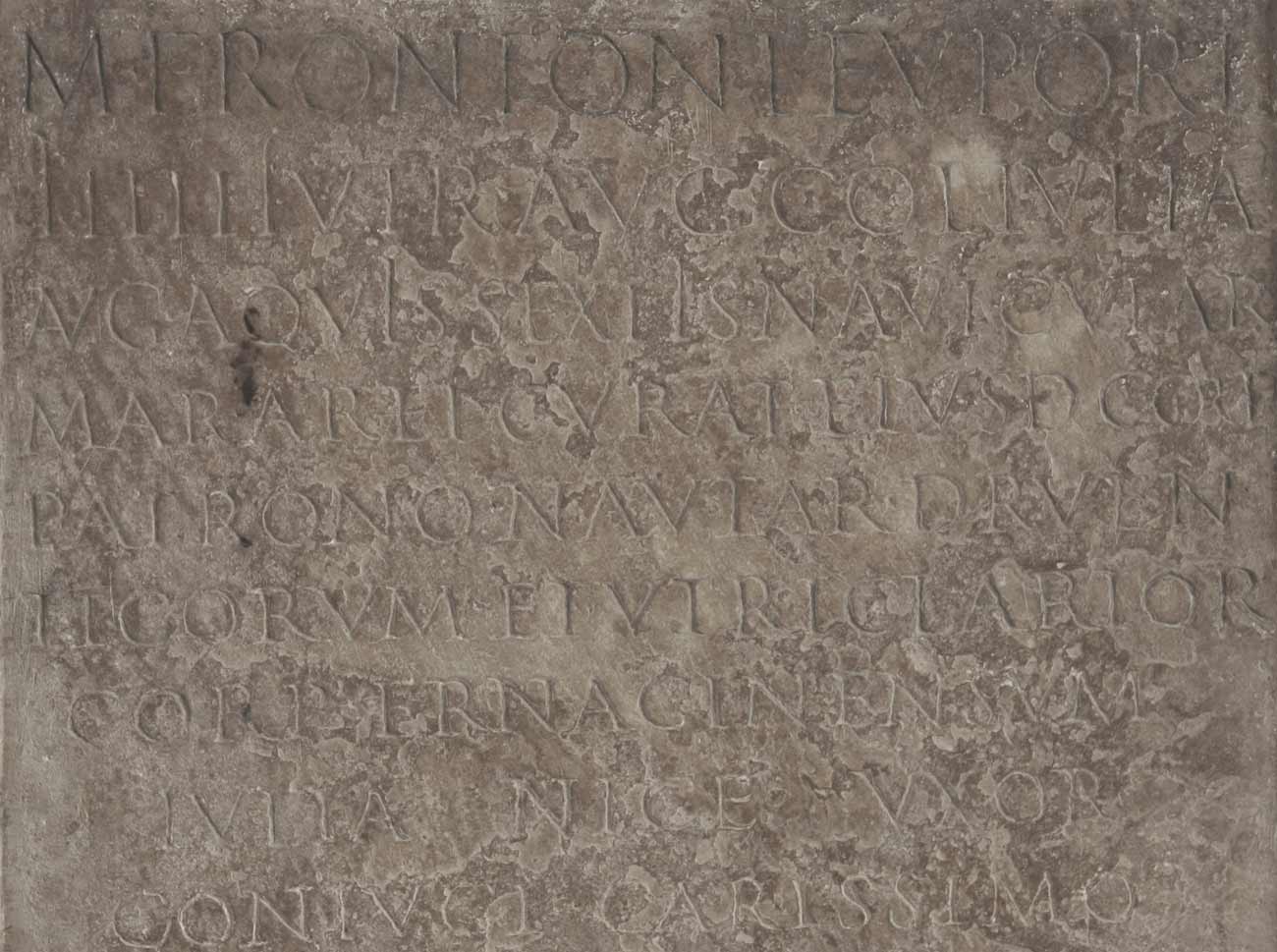

The fact that on the memorial stone Marcus Frontonus Euporus was at one

and the same time master of the boatmen and of the watermen (utriculaires – a

bladderwort plant) leads one to think that the utriculaires were transporters

who crossed the Durancole on floating rafts held up by inflated wine-skins. A

number of epigraphists support this theory.

During the 80’s a new theory appeared. The utriculaires were indeed

transporters, but by road. They would have used wine-skins on carts or beasts of burden to transport wine and oil between the plains of the

Durance and those of Arles.

Who is right ?